The Irish Border and Backstop Explained

The Irish Backstop dominates the discourse like it was Bake Off and these were normal times. In this resource, I wanted to do a step by step guide to understanding the Irish border, why Ireland insists on a backstop for it, and why that’s so problematic to some in the UK.

A big thank you to Mr Aodhán Michael Connolly (@MichaelAodhan) of the Northern Ireland Retail Consortium for his help in making me, and this article, less stupid. Any residual stupidity is in spite of his outstanding assistance.

First question, why are goods borders?

Great question, terrible grammar.

Goods borders exist to provide governments a level of oversight of what products enter the territory of their trading regime from another. Trading regimes can be a country’s territory, or a larger area like the European Union, within which common rules apply and movement within which isn’t considered by those who run it to be an import or export.

Why do governments want this oversight?

Because they want to be able to vet stuff entering their territory, including to confirm the entering good meets all local standards and has paid any required fees and tariffs.

So, they dig through every arriving box?

No, in the vast majority of cases the checks consist primarily of paperwork. A truck or freighter arrives at a border packed full of stuff, and with all the forms required to move that stuff inward. The border officers check the forms are filled out correctly and seem to broadly reflect what they’re seeing, and once they’re satisfied they let the container in without opening and searching it.

To make sure this trust isn’t taken advantage of, they use risk analysis to select individual consignments for thorough searches. At most modern borders this happens about 1% of the time.

I bet there are exceptions, though?

Yup. Some trading regimes have determined that certain types of paperwork required to move select products across the border require additional testing which can only take place at the border itself. The most famous example of this is EU veterinary tests for imported meat and livestock, which must be conducted by an EU veterinarian basically at the border.

Ok, got it. So what’s the Brexit link?

The European Union is a single trading regime because:

The Customs Union eliminates internal tariffs;

The Common External Tariff establishes a single tariff on goods from outside the EU;

The Single Market harmonizes standards and rules.

If the United Kingdom leaves the EU in a way that also pulls them out of either the Customs Union or the Single Market (or both), it will become its own distinct trading regime.

This trading regime will need to establish goods borders at the places where goods previously entered from the European Union, and the European Union will need to establish goods borders in places where goods previously entered from the United Kingdom.

One of these areas is the border between Northern Ireland (part of the United Kingdom), and Ireland (part of the European Union).

So why won’t Ireland and the UK just build borders then?

They still might, but they really don’t want to. There are two reasons.

First, historic political.

Northern Ireland has a grim and blood-soaked past. Those in Northern Ireland who wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom and those who wanted independence and perhaps unification with Ireland clashed violently with one another and with the UK government.

The violence was eventually halted in a historic peace settlement referred to collectively as the Belfast Agreement or Good Friday Agreement (GFA). The GFA represented a complex compromise, in part relying on Northern Ireland’s remaining politically a part of the United Kingdom but remaining heavily integrated into the island of Ireland.

There is a concern the building of any kind of goods border infrastructure at major crossing points from Northern Ireland into Ireland could reignite violence on the island.

Second, economic.

The economy of Northern Ireland is heavily integrated and intertwined with that of Ireland. There are products produced on the island which cross the current (invisible) border up to half a dozen times as they move from raw materials to finished goods.

If every one of those cross-border movements requires the preparation of paperwork, the presentation of that paperwork and potentially the paying of tariffs and other fees, the businesses which rely on these movements can rapidly become noncompetitive as costs and delays render their processes more expensive and slower than their competitors.

Even simple cottage pie made in Northern Ireland can undertake 7 border movements before it is the finished product. This includes the milk for the cheese topping which is from Northern Ireland but travels across the border to be made into cheese and then back to top the pie.

You can really taste the neoliberalism in every forkful.

That sounds bad. Can’t the UK and Ireland just… not?

So in a way, that’s the United Kingdom’s Plan-A in a No-Deal. Should the United Kingdom leave the EU without a deal in place, it has said it will simply not introduce any additional checks at that border, nor attempt to charge tariffs at it. In other words, with the exception of torture tools and biochemicals, the UK is going to act like nothing has changed.

So, problem solved then?

Not by a long shot, I’m afraid.

What the UK is essentially doing is accepting a degree of risk no other major country is willing to accept at a major border crossing. It is:

Assuming that goods standards in the European Union, which it will no longer help set or administer, will continue to be sufficient to protect UK consumers;

Accepting the existence of a backdoor past its tariff regime for EU products;

Assuming no 3rd country will make use of this backdoor.

That might be acceptable in the short term, but it’s a bandaid when what’s needed is a limb replacement. There is a genuine concern that while some businesses will follow the rules, many will not, undercutting those doing the right thing and making a mockery of the rules.

What about Ireland, is Ireland planning on doing the same thing?

Here’s where we come to the crux of the problem.

While the UK might be willing to accept the risk described above, the European Union doesn’t seem remotely as keen. The integrity of the EU Single Market and Customs Union is integral to them, and they will be very reluctant to accept a giant gap in its outer armor.

So, what will they do?

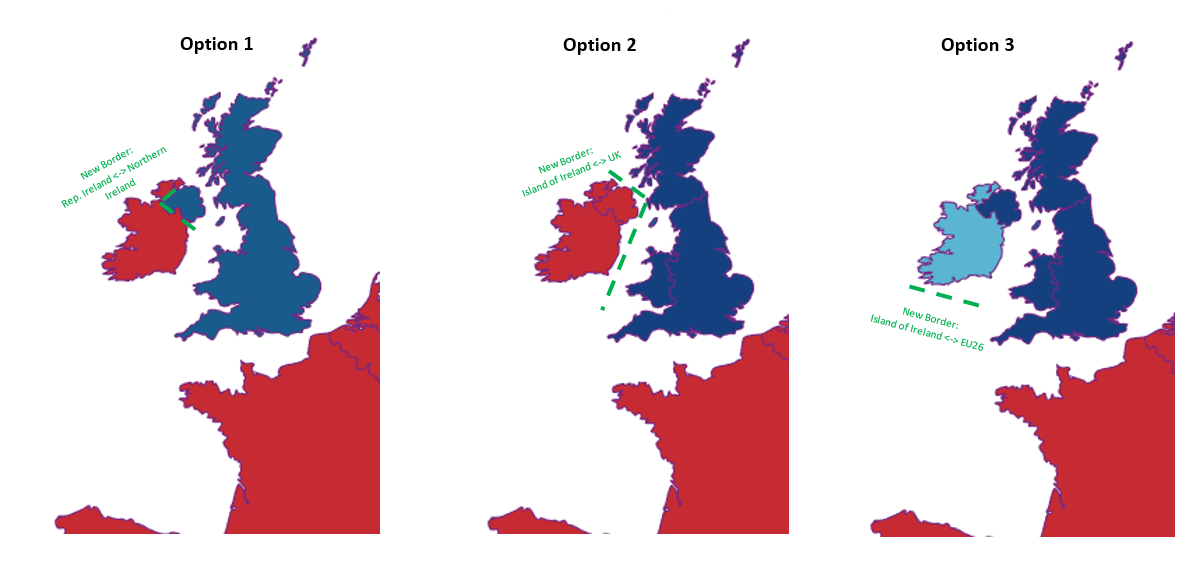

Following Brexit, there are three ways the European Union can prevent entry into its market of goods without clearance passing via Northern Ireland. It’s all about who is in which trading regime.

Option 1: Ireland remains in the EU trading regime Northern Ireland becomes part of the new UK trading regime. The EU then demands Ireland establishes a goods border where the two meet.

Option 2: Ireland and Northern Ireland remain part of the EU trading regime, and a goods border is established in the Irish Sea to administer goods moving between any part of Ireland and the new UK trading regime.

Option 3: Northern Ireland becomes part of the new UK trading regime, but no border is established. To prevent ‘contamination’ of its market the EU establishes goods borders between its other 26 Members and Ireland, effectively (partially) removing Ireland from the EU trading regime.

“Oh. Oh shit.”

None of those sound great.

Yup.

We’ve already discussed why Option 1 isn’t great.

Option 2 would require the UK to have part of its own territory effectively governed in a range of trade relevant areas by a bloc it’s not even a member of, while making internal UK trade a lot more painful.

Option 3 would cut Ireland off from some of the biggest benefits of European Union Membership from a trade perspective, without really addressing the fact that Ireland and the UK would have two different trading regimes with no border between them.

So what is Ireland doing about it?

Ireland and its partners in the European Union are insisting on the so called “Irish Backstop”:

Well done on first mentioning that like 7 pages into an article with “Irish Backstop” in the heading, but sure, what’s that?

I hate you.

The Irish Backstop is a provision which emerged from the negotiations over the UK’s Withdrawal Agreement with the European Union.

Concerned about a UK refusal to pursue Option 2 putting Ireland into a position where it has to choose between options 1 and 3 above, the EU insisted on a ‘backstop’.

This backstop would mean that if at the end of the two year transition period (during which everything stays as it is now) an agreement hasn’t been reached which makes Option 1 acceptable to both sides (ie, minimizes political historic implications and ideally, economic disruption) then Option 2 would apply.

In other words, if a way to make the Northern Ireland border work hasn’t been found, they’ll wack a border in the Irish sea instead.

The UK under Prime Minister May couldn’t accept this, because it saw Option 2 is unacceptably splitting up the United Kingdom.

So what happened?

The EU reluctantly agreed that rather than Option 2, the backstop would instead apply to the entirety of the United Kingdom. In other words, if at the end of the transition period a way to make Option 1 work hasn’t emerged, the entirety of the UK would remain within the EU trading regime in all the ways required to eliminate the need for a goods border.

I see, and why is that unacceptable to Parliament?

A significant number of Parliamentarians who are otherwise very supportive of Brexit have refused to accept the Backstop. This has proven sufficient to prevent the passage of the Withdrawal Agreement through Parliament.

Their concern is over how the determination of what constitutes an “acceptable Option 1” is made. Under the Withdrawal Agreement, it’s a decision made by consensus. The EU27 and UK would have to jointly agree an acceptable Option 1 has emerged. Until that happens, the Backstop would remain in place and the relevant EU rules would apply UK wide.

MPs have signaled that without the ability to leave the Backstop unilaterally, the UK could be trapped in it forever by an EU that, either maliciously or simply through impossible standards, refuses to accept any Option 1 as ‘good enough.’

What do these Parliamentarians want?

They don’t all speak with one voice, but the general consensus seems to be that they want the Backstop either removed entirely, capped with a time limit or amended to introduce a mechanism whereby the UK can exit it without the EU’s consent.

Is the EU likely to accept that?

The EU has thus far said it isn’t, including at the highest levels. For the EU, this would be to transfer the ‘risk’ and difficult decision (between Option 1 and 3) onto Ireland. This would be seen as a betrayal of a smaller Member State by the big players, which is not a great look for the EU.

The EU are reluctant to accept a negotiation premised on the idea that it is engaged in a conspiracy to exploit the region’s complicated history to trap the UK forever in its customs and regulatory zone.

And what happens in a No-Deal?

Unfortunately for everyone involved, a No-Deal scenario just brings everyone back to the three options above, except two years earlier because there’s no transition period and with everyone angrier and things breaking left and right.

Can technology save us?

If this show has taught us anything, it’s that technology holds benign resolutions to all of our problems with no side effects or consequences of any kind.

Anyone attempting to implement Option 1 (a border in Northern Ireland) might be able to use technology to reduce the amount of infrastructure required, to move some of that away from the border and to minimize the amount of actual ‘paper’ involved in border paperwork.

To date however, technology alone has not eliminated the need for border infrastructure at any major commercial land crossing in the world. Even highly advanced countries with great relationships like Norway and Sweden or Switzerland and its neighbors have borders with extensive physical infrastructure and procedures which take time and cost money (directly and indirectly) to navigate.

The EU has therefore been unwilling to accept removal of its backstop insurance policy in exchange for the promise a technological solution will inevitably emerge. It argues those who believe a technological solution is imminent should have nothing to fear from a Backstop such technology will either prevent, or swiftly allow the UK to emerge from.

This all sounds really hard, what’s going to happen?

I honestly don’t know how this will all shake out.

It does however promise to be complex, painful, and irritating for everyone involved, so I hope there’s something good to drink in Ireland.

It’s green, so I’m just going to assume its Irish without doing any further research.

Thank you for reading, hopefully you found it useful.

As a gentle reminder, ExplainTrade.com is a free service I provide without a Patreon or GoFundMe. Instead, I use this website as a platform to sell my services as a trainer in negotiation skills, trade policy and accessible communication.

If you or someone you know could benefit from some learnings, do get in touch.